A Gallipoli Memoir

Bert Sullivan’s first-hand account of the Gallipoli campaign, which took place 110 years ago

April the 25th is Anzac Day in Australia, commemorating the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign in the First World War. My grandfather, Herbert Sullivan, wrote the following narrative about his experience at Gallipoli as a 17-year-old Royal Marine.

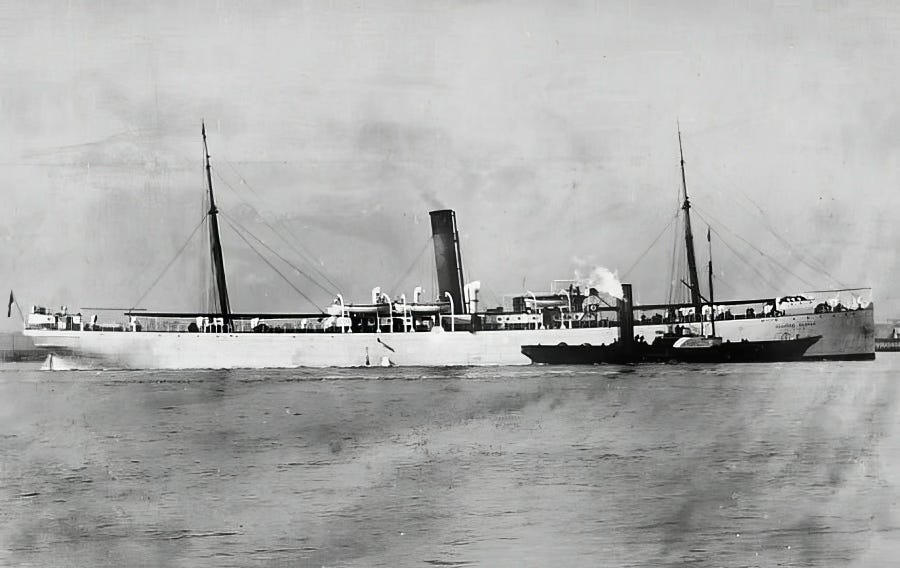

The Alnwick Castle troopship

Leaving Skyros in April 1915, the troopship Alnwick Castle sailed for Lemnos, the main base for our future operations in Gallipoli. The port was Mudras, and I do not suppose it had ever known so many varieties of ship in its history. There were British and French battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and gunboats, even the five-funnelled Russian Askold. Add to that the fleet of transports carrying thousands of troops that were to do the land fighting when the Navy had done their bit.

It was three or four weeks before all of the ships were properly laden, horses had all their hay, and guns had all their ammunition and other gear on the same ship. The Navy kept moving in and out, and we were told they were shelling the forts on Gallipoli so that we could land and casually March to Constantinople. How wrong they were! The Navy did not force a passage through the Dardanelles, and the army had to fight its way ashore. Of course, this was unknown to us at the time, and we still had ideas of being in Constantinople in a week or two.

In April 1915, out in the Aegean, the ships rolled and ducked, with destroyers dashing around like hens keeping an eye on their brood. After two or three hours sailing from Lemnos on the Alnwick Castle, we Marines finally got our first sight of Gallipoli. There were low hills in the distance, and as we got nearer, there were transports moored at intervals in front of us. The Navy was bombarding the coast, as we could see the flash from the ships and clouds of smoke appeared on the shores and hills about a mile or two from where we had stopped. It was quite exciting to us youngsters to see large battleships bombarding enemy forts. It seemed impossible that anything could stand the hammering the Navy was dishing out.

Panoramic view of the Entente fleet in the Dardanelles, April 1915

Relieving the Anzacs

As it got dark, several transports moved up the peninsula, our ship among them. We were in the Gulf of Saros, and the object of our visit was to keep the Turkish troops occupied while a landing was made further south. It succeeded up to a point, as the Australians had stormed ashore and got quite a good footing on the Gaba Tepe area before the Turkish commander realised we were playing cat and mouse with him and moved his troops to help those fighting the Australians. This put pressure on the Aussies, and us Marines were sent ashore to help. We were transferred from the transporters to destroyers, which took us as near as possible to the shore. We were then transferred to 14-oar cutters with picket boats pulling us into shore as far as they could go, and then we rowed the rest of the way.

When we landed on the shore, it was dark. Everyone had to carry something of use for our stay, and I was carrying half a side of bacon. It was very rough terrain uphill through the trees. As we moved in, the Australians were moving out to rest, and we went straight into their trenches and were in the battle immediately, facing the same enemy that we had kept waiting on what we learned was called the Bulair Lines. A liaison officer told us the Turks were about 750 yards away to our front, and as lookouts were posted, we had plenty of time if they made a move.

Of course, the Australians had already decided that the little boys sent to help them would soon lose all the ground they had gained. But they were wrong. We spent five days in the frontline and repulsed three attacks by rifle fire, and once we went over the top and chased them back to their trenches. We did not get a wash, and never had our boots off. When relieved, we still continued to help behind the lines, clearing up and patrolling.

We moved over to the left and relieved the NZ troops, and it was much quieter there. However, there had been some fierce fighting in this area, and volunteers were asked to patrol No Man's Land while others collected identity discs from the dead. Twenty-four of us, all Marines, offered to do the patrolling, and we spent all day and night eating hard biscuits and drinking water until the work was finished.

After 15 days, we were taken off, although the Portsmouth battalion had one last engagement, taking a hill where the Turks were worrying us with machine guns. It was a very brave action as the hills were steep and there was little cover. The battalion drove the Turks off the hill, but the cost was heavy and the casualties included their commander, Major Dickie Richards.

This ended our tour of duty with the Anzacs, and we joined the Alnwick Castle again and sailed south. There was plenty of activity in this area when we arrived. Shells were bursting in the hills where we supposed the Turks would be, but there was also plenty down on the plain, where our troops had to pass to reach the fighting area. A ship, the River Clyde, had been run ashore to form a breakwater, and troops passed through her to reach the shore down a ramp.

Landing at Gallipoli, Charles Dixon (1872-1934)

Cape Helles

We left the old Alnwick Castle for good and were moved to the River Clyde. From there, we marched ashore at Cape Helles, which was the southern tip of the peninsula. The beaches here were a hive of activity, as boxes of ammunition were being unloaded and dumped under the cliffs. We tramped down to the lower ground, and a field about two miles inland was selected as our ‘home’. We were instructed to dig holes for dugouts as quickly as we could. Our platoon Sergeant remarked that we would probably dig faster if the Turks started shelling the area, which they promptly did.

We finally got settled down, and found we were about halfway between the southern beach and the frontline trenches. After a spell working helping to build piers and communications, we had a spell in the trenches, and came back to find a Scottish regiment had taken over our dugouts, and some fresh ones had been found for us. As we had been shelled twice in that area, we did not mind, so long as we did not have to dig anymore. The area under our control was fast becoming a warren of burrows, through which we were constantly creeping with our heads down.

One of the jobs all units had to help with was the digging of a deep, wide trench to enable relief and transport to get up to the front quickly and safely. It was a boon to the troops, although now and then a shell found its way in to dispel our sense of security. Another job during our ‘rest’ period was the building of a complicated network of trenches, about two miles behind the front line, and the point beyond which we never were to retreat. This was known as the Eski Lines, and the only time the army crossed this point in retreat was when it was decided to leave the peninsula altogether on January 8th 1916, by orders of the powers-that-be in England.

On the peninsula, we just carried on doing what we were ordered to do, wondering how long it would take before something hit you and gave you the chance of getting away from this death trap. The area we occupied was only five miles square, and the Turks could shoot at every part of it from the higher ground leading up to a hill known to us as Achi-Baba. We were short of the heavy armament needed to dislodge them, as, having got us onto the peninsula, the Navy deserted us because of reports of submarines in the area and after losing three ships while moving up the Dardanelles. The Majestic was left behind when the Navy went back to Lemnos, but the next morning, May the 27th, it was hit by a German U-boat and turned over with just the keel showing above the water, remaining like this for months afterwards.

We could have done with the firepower of the Navy now, though, which would have made all the difference. So, it was left to the army to struggle on, gaining a couple of trenches in one sector and losing them in another. The casualties were heavy, as those who did not fall to Turkish bullets went down to diseases caused by flies and mosquitoes, and we began to wonder who was our real enemy, Turks or flies.

Sometimes it was not possible to get to the bodies lying in the open ground, and as the temperature reached up into the 90s, the smell can only be imagined. If a man tried to move onto the open ground, he stood a good chance of being potted by a sniper, so we moved around like moles below the ground and were getting more lice-infested every day. We tried washing our lousy underclothes, but there was a shortage of water, and if you left them on the sand to dry, thousands of insects held dancing classes on them. When we received permission to go to the nearest beach for a swim and a wash, the mosquitoes followed; some settled on the clothes you had taken off, and the rest chased you down to the water, having a bite here and there.

However, the water was always nice and warm, and life seemed worth living again. That is until the Turks found out we were really enjoying ourselves, and, of course, that could not be allowed. They sent shrapnel over and, as we did not want to be shot and drowned at the same time, we made for the beach again and chased the flies off our clothes.

Herbert Sullivan, 1917, aged 19

Down and out

As the months went by, hundreds of men were being killed in the various actions, and mates would suddenly disappear and you did not know where. The rest of us just carried on, and wondered how long our luck would last. By this time, it was obvious that no one was winning anything. The Navy did not come back in force, and the old Majestic still lay keel upwards off the beach at Cape Helles. A harbour of sorts had been built in that area, with the old River Clyde forming one side of it. It was not the healthiest spot to be in, as the Turks could reach it from the Asiatic side of the Dardanelles. Boats got in and out as quickly as possible.

To try and break the stalemate, in early August, a new landing was arranged at Suvla Bay in a place called Salt Lake (but there was no lake there at all). The troops used were straight from England, and apparently had no experience at all. The landing was a disaster from the start, and instead of easing things in our position in the south, we were treated to some of the heaviest attacks we had faced, and everybody was wanted on the front lines. We had only been down from the front trenches a couple of days when we were ordered back to a position on the left of the French troops. We now had to walk three miles to the front again, and on the journey we had to pass one of our batteries, which was having a game with some Turkish guns (you send one over, and we will send one back).

One of the enemy shells dropped right in our path, and I lost a few more mates. Several of my section were blown off their feet, including me, but with all the dust and smoke it was impossible to tell what was happening.

There was a lot of shouting near us, and when the air had cleared, the Sergeant called for everybody that could walk to move to the front, and although I felt something was wrong with my right knee, I was able to walk, so I went forward with the rest. When enough men had collected we moved onto all the frontline, where we were expected to take up a position, leaving behind a lot of mates we would never see again. I limped along with the ‘fit’ ones, half of them with brains so muddled they did not know where they were going. My head was clear enough, but my knee was hot and aching.

When we got up near the firing line, we were not needed, apparently, so after sitting about waiting for further orders, we were moved back again, finally arriving at our old dugouts. I was told to pack a haversack and make my way up to the casualty clearing station for an examination. The pain had now reached the groin on my right side, and the medical officer asked me what I was limping for. I told him about the pain, and he told an orderly to take my temperature. I was put to one side with some other injured men.

Soon after, this party, including me, were put into a transport wagon and taken to the hospital near the beach, and I was put into a bed in the canvas tents, the first time I had been under cover for seven months. The Turks shelled the area that night, which did not do anything for our peace of mind; however, we survived the night, and next morning, after another interview with another doctor, some of us were moved down to a ship in the built-up harbour, and we left Gallipoli with no regrets.

Grandad went on to describe his slow recovery and the rest of his WW1 experiences, stationed on the HMS Albion in the port of Grimsby. If there’s sufficient interest, I’ll post his further adventures later.

Thank you for sharing that—your granddad could sure tell a tale! I’m curious what his injury was.

This line popped out: “if you left [clothing] on the sand to dry, thousands of insects held dancing classes on them.”