How I Became Foreign, Part 20 - Foreignness Complete

Nostalgia, cats, and finishing touches

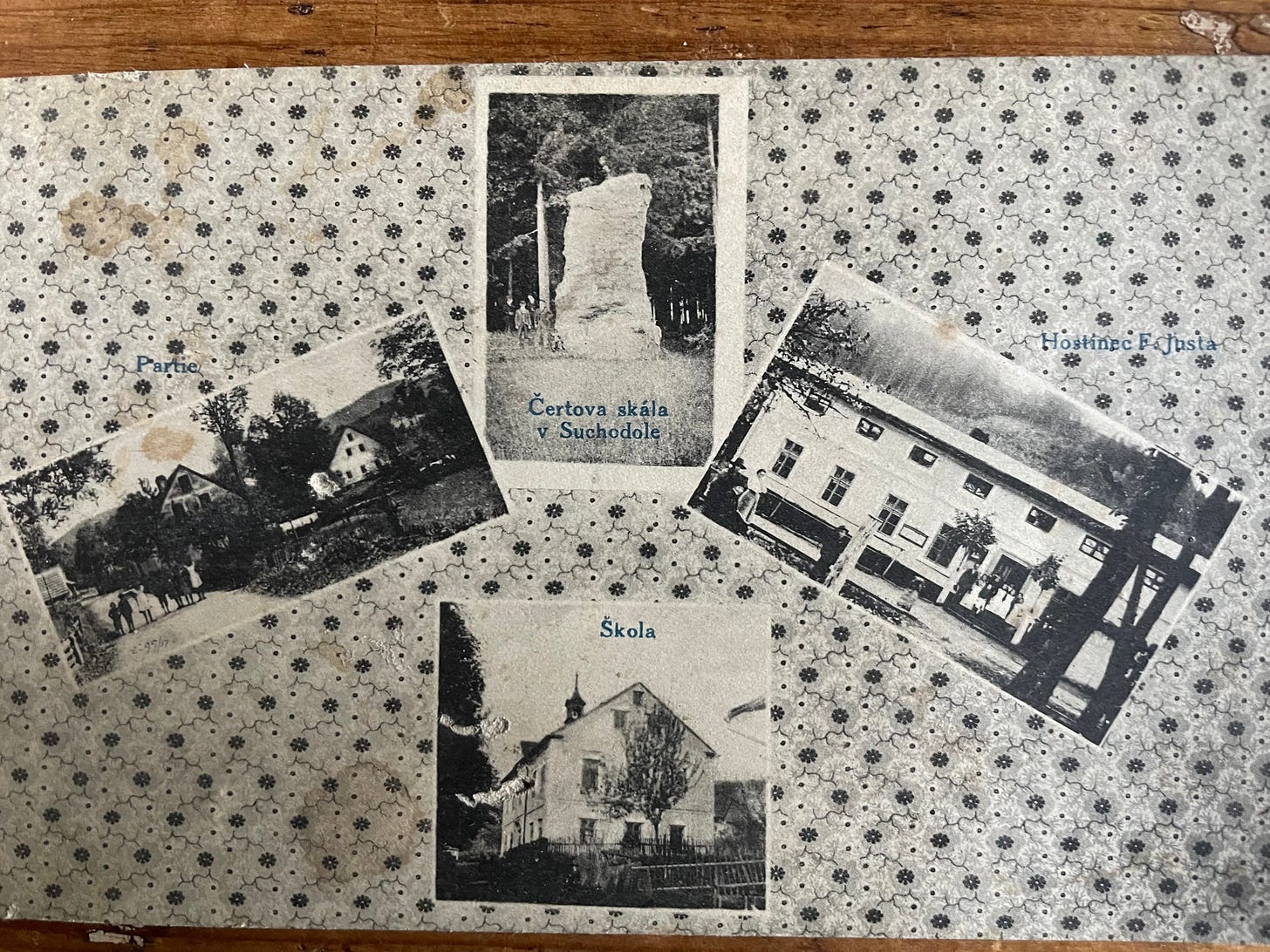

1900 Biely postcard - Ours is the house on the right

I lifted the coffee cup and noticed the inadvertent symbol of CND in the froth. The logo transported me back to university anti-nuclear protests, Greenham Common banners, and CND badges, without which no lapel was complete in the early ‘80s. Happy days of imminent nuclear obliteration, underlining the ridiculousness of nostalgia. The frothy message disappeared as I sipped my way out of cheery armageddon and back to the present.

Fat chance of any nostalgia here. We had long run out of money to make further major structural statements in the house, but when we called time on this first phase of building in 2023, we had managed to shape five bedrooms, two bathrooms, an office, a washroom and a combined living, dining, kitchen and piano-playing area that was a pleasing mixture of traditional and weird. Of course, when I say “we”, I mean Magda. My own part in the shaping of the building consisted of editing and writing, playing the guitar, drinking too much tea, and courting a growing sense of detachment.

In addition to the living areas, there was also a magnificent, vaulted hallway the size of an English flat, with adjoining workroom and boiler room-cum-store. There was a daunting amount of building left to tackle, but at this point we were not convinced the remaining work would be completed in our lifetimes. And, let’s face it, if we didn’t complete it, no one else was going to be silly enough to attempt it.

During one long summer when we were still embroiled in the offspring-related misdemeanours that had engulfed us, Magda tackled the garden while Theo and I swanned off on a series of mini holidays. She began by building two drystone retaining walls, initially using the ton or so of stonework that had been salvaged from the wilds of the two gardens. Some of the stones were the stunted monoliths commonly used in local fencing 200 years earlier, with deep grooves on each side to hold wooden posts. A few of them were broken, but there was a pristine minimonolith too. The damaged ones were incorporated into the stone walls as sturdy bases, and the unbroken one was planted with alpines. I can imagine future archaeologists searching for ancient property boundaries being really pissed off at all the upcycling.

Magda worked on these walls with the vision and work ethic of Merlin (and I should add a footnote here explaining that Merlin, according to legend, transported Stonehenge from Ireland to Salisbury Plain). In the process, she acquired the physique of an Olympian athlete, summoning her inner Hercules to move and position rocks that I couldn’t even persuade to wobble gently when applying all my strength. A neighbour later told us how an image had spread through the village like water through a roofless former hotel – an image based on a passerby’s observation of Magda shaping rocks with a circular saw while her male partner was hanging out the washing. The fact that, having completed the laundry, I went indoors to cook a meal, spoke of a healthy absence of gender stereotyping in this household. After all, part of becoming a foreigner involves inspiring amazement and disapproval amongst the locals.

We were living with our second cat by now. The original one, Cheech, had been installed to deter the mice, which had returned in force after their earlier disappearance following rumours of poorly fitted doors on food cupboards and a household with a penchant for smelly cheese. Cheech took his work seriously, and having shown several mice a thing or two, his mere presence decimated the rodent population. But then Cheech decided to move out.

He had been fond of following Theo over the river to a friend’s house, and the friend’s family, quite rightly, thought he was a lovely beast (the cat, not Theo). The inevitable happened – they began feeding Cheech, and he befriended their pet Schitzu, regularly accompanying the household on their dog walks like an unbidden chaperone. To make Cheech more comfortable during his visits, our friends purchased a new cat cushion and plonked it in a cosy spot near the stove. When our erstwhile pet stopped coming home, we sent Theo to apprehend him and drag him back in chains, but he was now too fond of his catnappers. We still see him regularly, and he is greeted like an old friend; but he is not so keen on coming indoors now that Cheech 2 has been installed.

The second cat (who we renamed Rishi after Cheech 2 lost its appeal) had followed Theo home from the pond at the edge of the village. No one in the village (not that we asked very many people) knew where he might have sprung from, so we held onto him until his rightful owners turned up to claim him, like one of the toys in the window of Bagpuss and Co. Luckily, no one did, and Rishi continued where Cheech had left off, deterring mice, charming everyone, and occasionally shitting on the houseplants.

The new tiled stove was part folly, part time-travel, built by a specialist stove-builder who had last updated his construction manual in 1700. He worked in abstemious silence over two days, refusing to be tempted by such fripperies as coffee and conversation. He even refused to be paid for six months after completing his work. Our attempts to contact him were unsuccessful, and his stove show room had such obscure opening hours that it was, in practical terms, permanently closed. I became convinced that the shop had locked its doors for the last time long ago and that our new-but-ancient stove was the bizarre result of a time-slip conjured by stress and strong tea.

Exactly six months after the stove was completed, a hand-written invoice materialised on the doormat. We withdrew the requisite sum and drove immediately to the stove shop on the outskirts of Narnia. It was bright in the snow, lights blazing, its window display of tiles and ovens pristine. We greeted the stove maker like an old friend, congratulating him on his splendid anachronistic work, which had brought our house to life and centred the whole living space. He thanked us and bid us goodbye - three words in total.

When next we passed the stove shop, it was dark and shuttered and had clearly not opened its doors since the early 18th century.

With the stove ablaze, complete with an elevated bed at one end, the concluding waves of building-related work rose and fell, a gentle sequel to the chaos of stone, brick and plaster that had gone before. These final installations all involved wood. A staircase, rising at a right angle from the top of six wall-hugging concrete steps was fitted, along with railings on the landing that meant we had missed the opportunity to plummet to our deaths through the long-standing hole in the floor. The garden shed-cum-greenhouse was also fitted with a Magda-designed wooden front and repurposed doors and windows. This wooden part of the project seemed light, warm, carefree, compared to the ice, coal and dust of previous years. The only hiccough came when the team fitting the frames around the holes in the bedroom walls that would eventually be doors turned out to be uncertain in their craft.

The leader of the two-man team tacked the frames together on the landing on a trial and error basis. One side would be fixed, and the other would fall off; the broken bit would be refixed, and the other bit would clatter to the floor. When the third of these recalcitrant frames was being hoisted into place, the wood lurched drunkenly from one side to the other. The man made a leap for his goal, attempting to pin the wood in place before it fell. His assistant jumped in to help, but the frame made a 180-degree twist, wrapping the team leader in its wooden coils. In an instinctive panic, he lashed out, and the broken pieces of former frame fell to their ruin. Each door frame misbehaved, and by the end of the process the men were arguing with each other, swearing at us, and vowing never to set foot in our house again. But the Czech Chuckle Brothers had certainly provided good cabaret.

This was one of many moments when we were reminded that cutting corners by hiring people who don’t really know what they’re doing scores highly on comedy but is not, in the end, a good investment. We had to redo all the door frames apart from one, a surviving structure that fell off a few weeks later when Jan slammed his door a little too enthusiastically.

And with the door finally slammed on Phase One, and with the understanding that there may be no Phase Two, it was time for a long break. We revisited that offshore western European island we had vacated several years earlier and caught up with friends and family, no matter how fast they tried to run.

I felt oddly alienated back in the land of my birth, as if nostalgia had been revealed as thinly veiled lies. Absence had somehow stripped away the homeliness from our former home. I no longer felt I belonged. When, a few weeks later, we returned to Czechia, there was no real sense of home there, either.

And that, dear reader, is how I became foreign.