Odran – A Martyr of Life and Death

St Patrick’s charioteer and revelations from beyond the grave

Due to circumstances beyond my control, I share my birthday, 19 February, with the feast day of St Odran. Every day of the year has a few saints associated with it – my additional 19 Feb roster includes some splendid names: Saint Gabinusand (third-century Roman martyr), Saint Quodvultdeus (fifth-century bishop of Carthage), Saint Barbatus of Benevento (seventh-century bishop), and St Conrad of Piacenza (fourteenth-century Franciscan), but I am particularly happy to share the space with Odran. For starters, he was St Patrick’s charioteer.

This revelation demands a brief pause. The fact that St Patrick had a charioteer changes our perception of the man. Rather than the standard Catholic image of an elderly gentleman with a crook, mitre, and shamrock, patron saint of bar staff dressed as leprechauns, this charioteering Patrick is more like Charlton Heston sweating muscularly in Ben Hur. And the trusty sidekick behind the chariot reins was Odran, hero of February the 19th.

Odran has the honour of being Ireland’s first Christian martyr, murdered in the mid-fifth century. In one version of his legend, Odran gets wind of a plot to kill St Patrick and switches places with him on the chariot. An assassin hurls a spear at the man in the passenger seat, killing Odran instead of the intended Patrick.

In another version of the martyrdom, pagan King Lóegaire mac Néill tests the veracity of Patrick's Christian beliefs. Tired of the preacher rattling on about forgiveness, Lóegaire commands his brother Nuada to kill Odran. “Okay, Mr Turn-The-Other-Cheek, what are you going to do about that?” he cries (although you shouldn’t take this quote too literally). The murder is investigated at King Lóegaire’s court, leading to a complex legal decision balancing Christian and pagan law.

To punish Nuada means pissing off the king, but letting him off the hook would be an insult to Patrick and Ireland’s nascent Christianity. The judge of the case, Dubhthach, Lóegaire’s Christian-leaning Chief Druid, finds the perfect compromise. He rules that Nuada should be executed for the crime, with the consolation that his soul will be forgiven and ascend to Heaven. The case was a battle between religious and secular law, and its outcome is said to have led to fifth-century Irish laws aligning with Christian values.

(Serendipitously, it was on 19 February 1852 (St Odran’s feast day) that Rev. James Henthorne Todd and the Very Rev. Charles Graves submitted to the Irish Government a proposal for the transcription, translation, and publication of the Ancient Laws and Institutes of Ireland, which included the manuscript describing St Odran’s death and the ensuing court case.)

But this isn’t the most interesting of the Odran legends. The one that steals the show is the extraordinary tale of Odran of Iona.

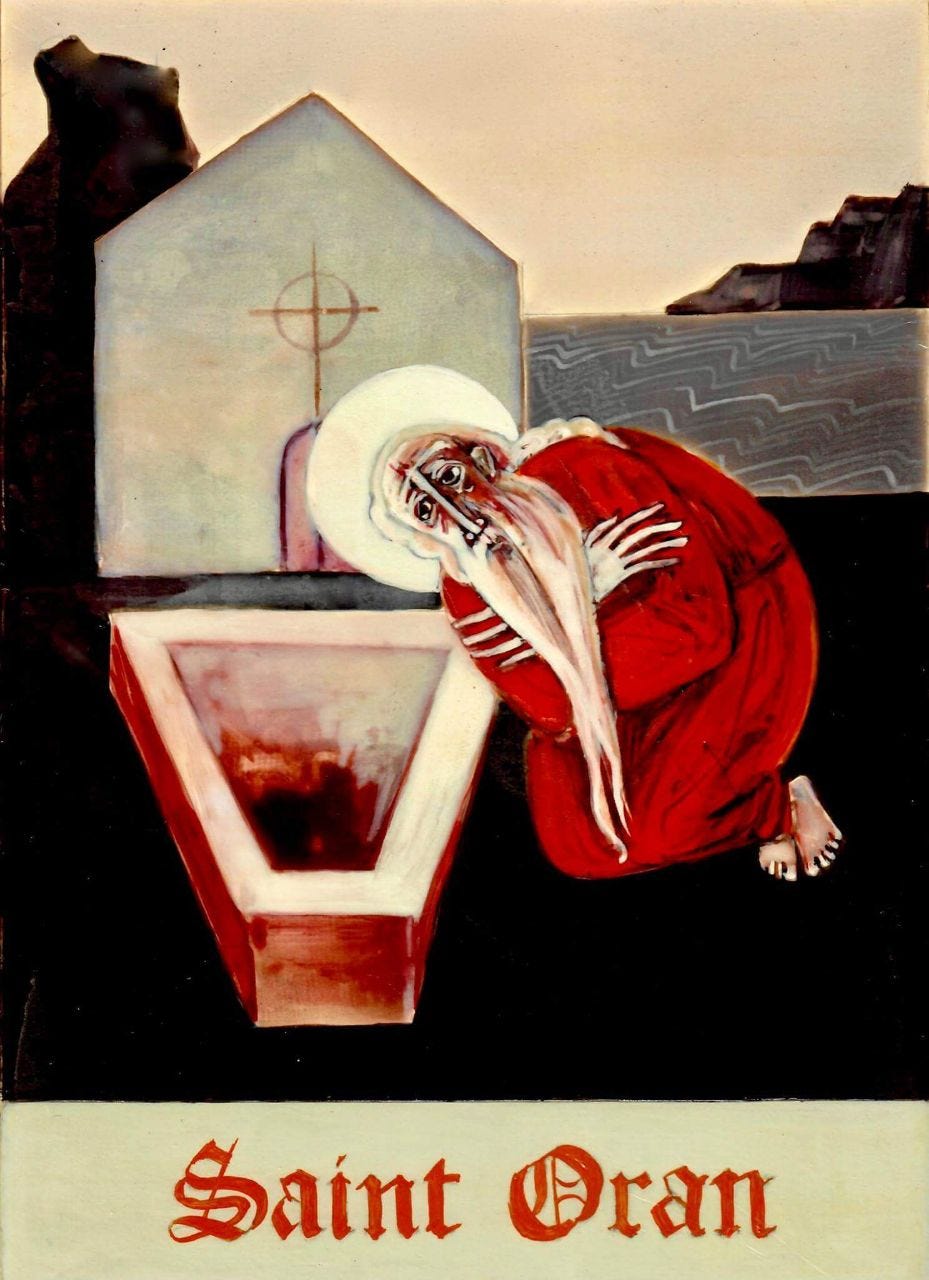

St Oran of Iona. From https://orthodoxmissionkenya.org/27th-october-feast-st-oran-iona/

The other Odran

Due to having the same name, St Odran – or more commonly Oran – of Iona has been confused with the Irish charioteer Odran. Iona’s Oran was alive 100 years after the murdered Irishman, but folklore and legend always play free and easy with timescales and chronology.

Oran, like St Patrick, was born in Britain but lived most of his life in Ireland. He was Bishop of Waterford at the time of his death in AD 563 and was one of St Columba’s twelve-man commune on the Scottish island of Iona. If you’re chasing him up online, bear in mind that he is sometimes called Odrioan of Waterford, Odrian of Iona, Odhran, Otteran, Oterano, and the very unfortunate Otteranus.

Columba and his men had arrived on Iona in 563, and Oran – probably in his 50s – died soon after and is buried in Iona Abbey. Post-mortem, Columba saw devils and angels fighting over Oran’s soul – the latter triumphed, and Oran ascended into Heaven. Columba dedicated the island’s first church to his old friend (now St Oran’s Chapel, part of Iona Abbey), and its surrounding cemetery is called Reilig Odhráin (Odran’s graveyard) in his honour.

But folklore has a far more interesting yarn.

Isle of Iona, St. Oran's Chapel doorway. Photo by Chris Downer. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

One in the eye for Oran

Columba had struggled to build a chapel on Iona – its walls collapsed overnight, undoing the day’s work. This wasn’t due to poor engineering and shoddy workmanship, of course – it was supernatural vandalism. The voices in Columba’s head told him the chapel walls would only stand if a living man was buried in the foundations. Oran, game for a last big adventure, volunteered for the human sacrifice job and was buried alive under the chapel walls.

Oran’s macabre motive was to assess the state of play in the afterlife. Columba, aware of this posthumous mission – the two men had often debated the nature of Heaven and Hell – completed his chapel and then, curiosity bettering him, ordered Oran’s grave to be opened. This was a tricky job, the corpse being lodged in the foundations, but the monks’ spades dug deep and scraped away the earth from Oran’s face. His eyes pinged open, a crowd-shocking trick utilised in countless horror films, and he began to rise from his grave.

“There is no wonder in death”, Oran declared. “Heaven is not as it is said to be, Hell is not what it is said to be. The saved are not forever happy, the damned are not forever lost.”

Columba acted quickly before Oran could spill more of the divine beans. “Pile earth on Oran’s eye!” he cried. The revenant was manhandled back into his grave and covered in earth before he could undermine the entire basis of Christianity – the notion of good and evil, redemption and damnation.

I have always found this mediaeval legend extraordinary. Oran’s rational insight would be more at home in the agnosticism, belief, and unbelief philosophies explored in the post-Darwin writings of Thomas Huxley (agnostic), Cardinal John Henry Newman (born-again Catholic), Bertrand Russell and Charles Bradlaugh (atheists and secularists), and writers such as George Bernard Shaw and Virginia Woolf. What is Oran’s rational insight doing here, 1,400 years before anyone else caught up?

Well, okay, the Oran legend isn’t actually contemporaneous with the first records of St Columba’s life, which were penned in the mid-seventh century. Oran first appears in the tale in the twelfth century – but that’s still 700 years before the debunking of Christian heaven and hell became commonplace.

This is simplifying things for the sake of brevity, I admit. Several pre-modern Christian philosophers have risked their lives by veering from the orthodox narrative (notably the early mediaeval advocates of apokatastasis, twelfth-century Hildegard of Bingen, and Martin Luther in the sixteenth century). But their stories are set in cloisters and scriptoriums, not in haunted graveyards after a human sacrifice.

Frustratingly, St Odran of Iona’s feast day is 27 October, not 19 February. But as Oran shows us, you can’t have it all your way.

It seemed to me a shame that there were no songs about Oran, so I wrote one a while back, with the imaginative title Oran. I then found that Stephen MacDonald had had similar thoughts in 2019 with his song Oran. Anyone fancy adding a third?

The so-called “Screaming Man” from Iona Abbey. Could this carving be linked to the Oran legend?

References

Paul Sullivan and Quentin Cooper, Maypoles, Martyrs and Mayhem (1994)

David Hugh Farmer, The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (1987)

https://anastpaul.com/2022/10/27/saint-of-the-day-27-october-saint-odrian-c-died-563-bishop/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odran_(disciple_of_Saint_Patrick)