I have a cherished memory of sitting in the sidecar of my Uncle Tony’s motorbike, driving along the seafront at Cleethorpes and looking up at lions and baboons perched on the rocky outcrops of Cleethorpes Zoo. These are the kinds of memories that help keep childhood vividly present.

There are two problems here – I was never taken to the zoo on a motorbike and sidecar, and there are no rocky outcrops from which animals would be visible from the road. I did occasionally ride in the sidecar, and I did visit the zoo, but the memory is a false one.

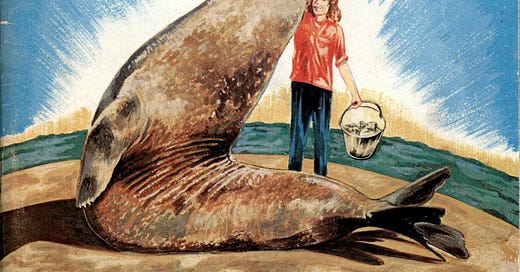

So, in recalling Cleethorpes Marineland and Zoo, which opened 60 years ago and closed 14 years later, I must rely on memories of a family visit in 1967 and a school trip in 1969. On the earlier occasion, my Dad had borrowed my Grandad’s cine camera, and he shot 30 seconds of grainy, Standard 8 mm silent colour film. A snoozing Elephant seal, a pacing Lion, nervous Flamingos, Humboldt penguins inspecting lifeless herrings, and Spoonbills feeding on something red in a bowl. I remember declaring “They’re eating blood!” and believing this to be the case, in spite of my parents’ protestations.

There were 30 of us on the 1969 school trip, a single class of seven-year-olds from Fairfield Junior School in Grimsby. The coach had picked us up from the entrance to the school drive, which for me was a two-minute walk from my back door. There was a general air of excitement, as on any school trip, but I was particularly animated that morning, telling everyone what we could expect to see, how Magog was the only Elephant seal in an English zoo, and how the baboons sometimes escaped and ran amok, pinching crisps and chips from the human visitors like ugly, bare-knuckle seagulls. I made up both facts, but when you’re on a roll and the material is running out, you just have to supplement it. Unfortunately, the zoo proved to be devoid of baboons, so I told my friends they must have been recently evicted.

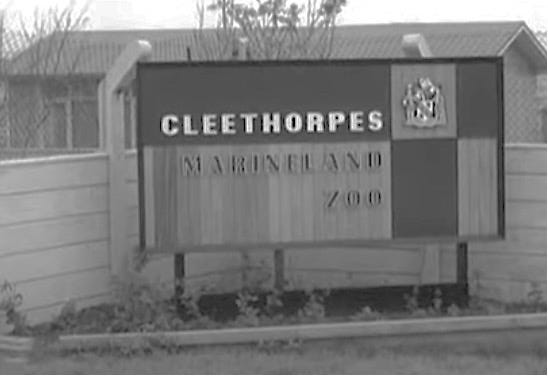

Arriving at 10.30 am, we were herded through the exhibits in a caterpillar of kids topped and tailed by a teacher, neither of whom were happy sacrificing their Saturday for the wildlife. We watched the penguins and pelicans mop up dead herrings. We asked the teachers if the sealions could be fed too, seeing as we had made the effort to turn up, but were gently let down. We were told not to go too near to the edge of the wildfowl lake. We were told not to run. We were also told not to throw sweets, sandwiches, or indeed anything into any of the cages.

After an hour and a half, we were told to occupy the benches outside the cafeteria and eat our packed lunches, while the teachers sipped plastic cups of tea and pretended we couldn’t see them smoking. This break took a frustrating half an hour, time that could have been spent ogling the Elephant seal. We now had just one hour left, as the coach was arriving at 1.30 pm, and 10 of those precious minutes had been set aside for a raid on the gift shop.

We finally made it to the enclosure of Magog the Elephant seal, but he was dozing like an overstuffed binbag, and many of our party were more interested in the livid pink flamingos next door and the opportunity to sing snatches of Manfred Mann's 1966 hit Pretty Flamingo. I was only allowed five minutes gazing at the prone Magog, but I consoled myself with the thought that I lived 30 minutes away from the zoo and could return soon.

The school party was growing restless now. Ostriches and Zebras held no attraction, and the birds and smaller mammals in cages were passed by with scarcely a glance. The trip through the well-stocked reptile house was a sprint, and we finally descended on the gift shop with our allotted spending money of half a crown (12 and a half pence). The shelves displayed a cornucopia of highly desirable rubber, plastic and plush toy animals and trinkets. I opted for a badge, a pencil, and a large rubber snake.

I seemed to be the only one who was sad to see the zoo recede in the rear window of the coach. As we pulled up at Fairfield School, someone piped up to say that the girl who had been sitting next to her on the outward journey had not made the return trip. The teachers panicked, blaming the girl and then each other and then everyone else for not spotting the obvious absence of Nicola Black.

The Sealion enclosure

We had to wait until Monday morning to find out what had happened. Nicola walked nonchalantly into the classroom, to the disappointment of those who thought she must have drowned in the wildfowl pond in despair. I interviewed her, interested to hear how she had reacted to being abandoned and how she had spent the extra half an hour in the zoo. She told me she had spent too long in the gift shop and missed the rallying call of the none-too-vigilant teachers. When she realised the rest of the class had left the shop, she wandered around the zoo looking for us. Had she seen the Elephant seal again, I asked? Yes, she said, and it was still lying in a dormant, fat pool of itself on its concrete beach. Nicola had not panicked but had waited by the zoo exit until the coach returned, as she knew it would. I was jealous, of course, as she had snatched extra time in the zoo. But would I have been so calm and clear-headed in the face of abandonment? I doubted it.

Later that year, Magog the Elephant seal ate a plastic bag that someone had thrown into the enclosure and died of digestive complications.

For reasons that elude me now, I only visited the zoo once more before it closed in 1979. If my family decided to visit a zoo for a day out, it was either Natureland in Skegness, Flamingo Park Zoo in Malton, or Belle Vue Zoo in Manchester. We would occasionally venture further afield to the likes of Windsor Park Zoo or – always a favourite – Woburn Safari Park. Consequently, I didn’t get to see the Killer whale, Calypso, a seven-year-old female caught off the coast of Canada, who spent six months at Cleethorpes Zoo between 12 December 1969 and 8 June 1970. She was relocated to Nice, and died in December 1970. She had almost bankrupted Cleethorpes Zoo with her prodigious fish requirements and a cocktail of pills deemed necessary for her health.

Calypso at Cleethorpes

Fibreglass pools and plastic animals

Cleethorpes Marineland and Zoo opened in 1965 as a satellite branch of Flamingo Park Zoo in Malton. The marine theme was its USP, and the site featured three interconnected 40-foot diameter decagonal pools made from reinforced prefabricated fibreglass panels. These pools – two of them eight feet deep, the other one 12 – were unique in their day.

The deepest pool was designed for dolphins (and, later, Calypso the whale), but was full of seals on my school visit. The two smaller pools saw a succession of hippos, seals, sealions, and the beloved Elephant seal. The ‘Marineland’ theme extended to the aforementioned penguins, pelicans, flamingos, spoonbills, and waterfowl.

The zoo was sold in 1977, and the new owners were criticised in the Grimsby Evening Telegraph for removing many of the living exhibits and installing plastic animals in their place. Although this would certainly have reduced the food and maintenance bills, the injection of plastic soul failed to save the zoo as surely as the ingestion of a plastic bag had failed to save poor Magog.

The enterprise staggered on until 1979, when star attractions such as Hercules the hippo were moved to new homes prior to the zoo’s closure. Hercules went to Dudley Zoo, following a fundraising campaign to pay for the complicated relocation. It was a journey too far for the animal, which had been moved to Cleethorpes from Belle Vue Zoo a few years earlier. He died a few months after arriving in Dudley.

The ill-fated Hercules

When the new owners of what was to become a go-kart track were working on the former zoo site in 1980, their diggers unearthed the corpses of several animals, including crocodiles and lions. Clearly, some of the beasts had failed to find new homes and were secretly killed and buried.

The go-kart track transformed into Pleasure Island Theme Park in 1993. The wildfowl lake and one of the fibreglass marine enclosures had survived the changing times, with sealions occupying the latter. But all is change in the tempestuous social and economic maelstrom of Cleethorpes, and Pleasure Island closed in 2016. The Jungle, a small offshoot of the zoo that opened in 1994, a stone’s throw from the parent establishment, closed in 2022.

These reflections hark back to days when zoos were primarily menageries. In 1969, only Gerald Durrell’s Jersey Zoo was seriously practicing something that all zoos now ostensibly pursue – conserving species through captive breeding programmes and educating the recalcitrant public in the process. Perhaps it’s no bad thing that hand-to-mouth, conservationless enterprises such as Cleethorpes Marineland and Zoo no longer exist. But as I linger here today with my youngest son in a 1990s Cleethorpes retail park of fast-food outlets and discount stores, within sight of the derelict Pleasure Island grounds, I still envy my younger self and Nicola Black. We had a zoo just around the corner, and that was a wonderful thing.