Detail from Southwark Fair (1733) by William Hogarth, showing “the Icarus of the rope”.

Robert Cadman achieved fame between 1732 and 1740 by establishing himself as a freelance steeplejack flyer and ropeslider. He first hit the headlines by "flying" across the River Severn in Shrewsbury on one of the earliest zip-wires in history. He fixed a rope to an anchor point in Gay Meadow, crossed the river to St. Mary's Church, and ascended the 68-metre-high spire, fixing the other end of his rope. After performing acrobatic stunts for the mesmerised crowd below, he descended the zip-wire wearing a wooden breastplate with a central groove for the rope and flew over the river to considerable applause and fame. The deed earned him the soubriquet “the famed Icarus of the rope”.

Cadman’s wife Judith collected money from the agog crowd, and spectators were also encouraged to send donations to the Cadman home in Shrewsbury or send notes inviting him to visit them for payment.

Cadman became an overnight celebrity, but his exploits and fame were not confined to Shrewsbury. He toured his dangerous one-man show through England in 1732, with notable appearances at Dover, where he "flew" across the harbour, and Lincoln, where he descended from one of the cathedral towers to Castle Hill way below.

In October, the show came to Derby, with Cadman amazing the crowd by sliding down a rope suspended between the tower of All Saints (now Derby Cathedral) and the bottom of St Michael’s Church, a steep descent over a distance of nearly 80 metres (262 feet). He performed this feat on his trusty wooden slide, using his arms and legs for balance. Halfway across, Cadman blew a trumpet and fired a pistol, and he moved so fast that friction-fed fire and smoke were observed in his wake.

Having descended, Cadman worked his way back up the rope, entertaining the crowd by balancing on and dangling from the zip-wire. After the hour-long ascent, he whizzed down for a second time, performing this feat on three successive days.

Derby Cathedral (formerly All Saints) seen from Irongate, by Andytrenier. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Derby saves its ass

During the brief “art of flying” craze, as it was dubbed, lots of people joined the airborne bandwagon and scaled the heights, attaching ropes to everything from walls, towers, and houses to trees, bridges, and poles, and either contriving their own means of descent or sending unfortunate animals down the zip-wire instead. If a human’s mixture of bravery, ambition, and stupidity compels them to engage in dangerous sports, fair enough, but roping in other species is unforgivable.

The “flying” craze in Derby came to an end in August 1734 when a man boasted that he would better Cadman’s performance of two years before. The challenger – recorded by tight-lipped posterity as “a vagrant” – attached one end of his rope to All Saints, as his predecessor had done, but fixed the other to the County Hall in St Mary’s Gate, a distance more than twice the length of the Cadman descent. Having secured his tightrope, the man-with-no-name then led a donkey into the church and coaxed it up the stairs of the tower. The poor animal was heard braying for several days at the top of the steeple, presumably a mixed cry for food and rescue.

When the appointed hour came, Mr A. Vagrant amazed everyone by descending the rope at speed, towing a wheelbarrow containing a thirteen-year-old, similarly nameless boy. Then it was the turn of the poor donkey. It was fastened to a wooden board, with lead weights attached to each of its legs to balance and secure it in a position worthy of the best torturer.

With the rope being slack, and the weight of the animal and its metal burden being considerable, onlookers had the impression that for the first part of the descent the animal was simply plummeting. The donkey then whizzed down the final hair-raising stretch towards County Hall. Twenty metres short, the All Saints end of the rope snapped. By this point, the animal was moving at a terrific speed, and it flattened several rows of onlookers.

According to local reportage,

He bore down all before him. A whole multitude was overwhelmed; nothing was heard but dreadful cries; nor seen, but confusion. Legs and arms went to destruction. In this dire calamity, the ass, which maimed others, was unhurt itself, having a pavement of soft bodies to roll over.

The plummeting rope at the All Saints end knocked down chimneys and injured more people. But although there were broken bones and blood aplenty, there were no reported fatalities. The heir of Cadman counted his blessings, but was unable to count his intended whip-round money, as a hasty exit was in order. The fate of the ass is not recorded. Its former owner left Derby and went into hiding before anyone could arrest him.

The Newcastle Courant had recorded a similar bout of donkey torture on 14 December 1733, recording the exploits of “The Flying Man” – possibly the same individual as the Derby daredevil, although there were a handful of similarly inclined young men bothering steeples at this time:

Newcastle upon Tyne, Dec 14. This Day se’night [i.e., seven nights previously], the Flying Man flew from the Top of the Castle into Bailey-Gate, and after that he made an Ass fly down, by which several Accidents happen’d thro’ the Carelessness of People not getting out of the way, tho’ a very great and timely warning was given; for the Weights ty’d to the Ass’s Legs knock’d down several, bruis’d others in a violent manner, and killed a Girl on the Spot.

Hogarth’s Southwark Fair (1733) - the full picture. Cadman is top-left.

Cadman’s Fall

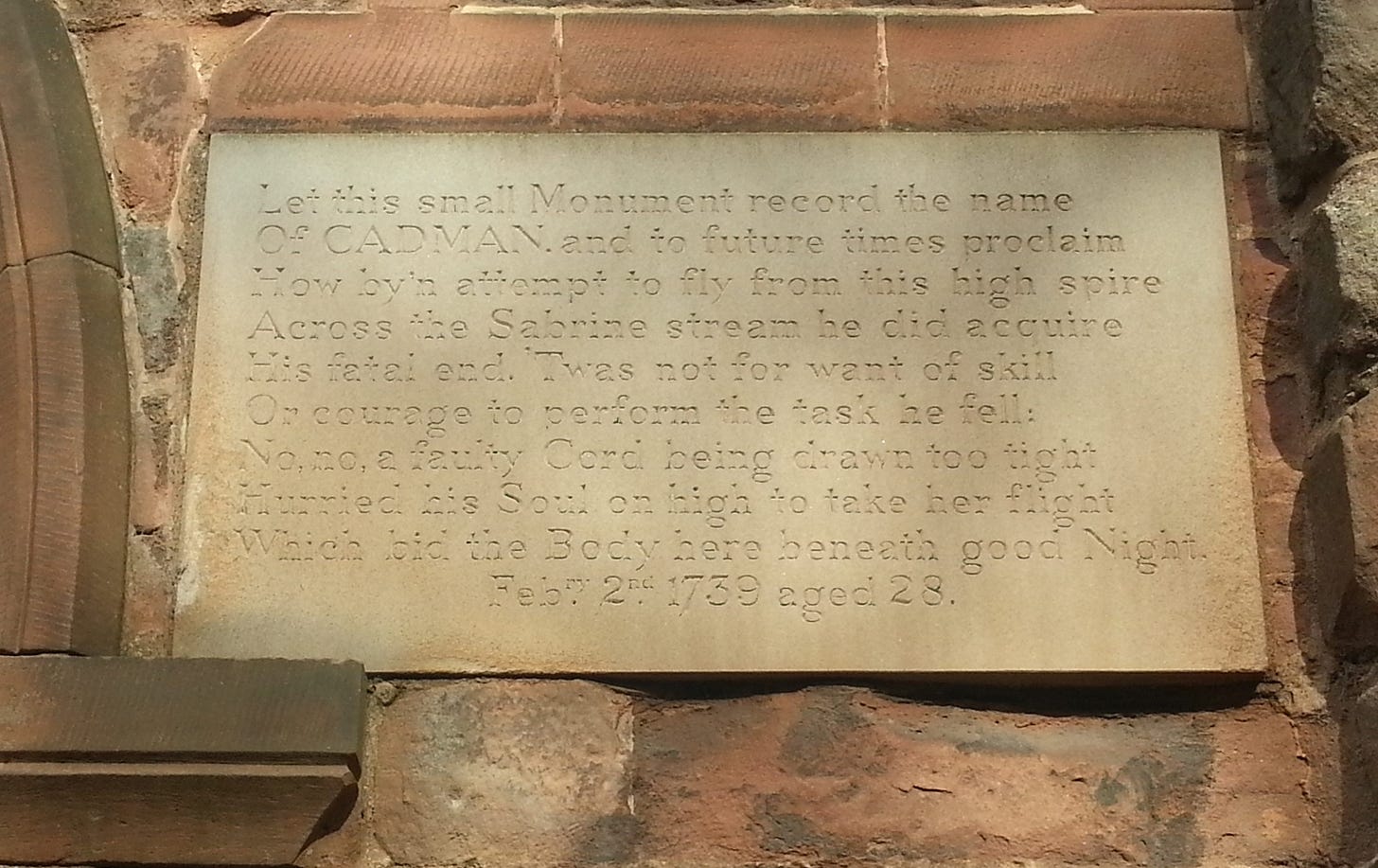

How, you may ask, did Cadman and his acolytes manage to keep their nerve, balance, and lives? Well, in Cadman’s case, he didn’t. In his hometown of Shrewsbury on 2 February 1740, aged 28, he fell to his death after an attempted repeat performance of his zip-wiring feat from St. Mary's Church. He is buried in the town, and his grave epitaph provides the details:

Let this small Monument record the name

Of Cadman, and to future time proclaim

How by'n attempt to fly from this high spire

Across the Sabrine stream he did acquire

His fatal end. 'Twas not for want of skill

Or courage to perform the task he fell,

No, no, a faulty Cord being drawn too tight

Hurried his Soul on high to take her flight

Which bid the Body here beneath good Night

On 7 February 1740, The London Evening Post reported that Cadman’s fatal mishap was caused “by the cutting off of the rope where it came through the steeple, it being fasten’d to the frames of the bells.” Writing in 1825, local historians claimed:

Just before he set out on his mad career, he found the rope a little too tight, and gave the signal to slacken it: but that the persons employed, misconceiving his meaning, drew it tighter. It snapped in two as he was passing over St Mary’s Friars, and he fell amid the thousands of spectators … after reaching the earth, [his body] rebounded upwards several feet … the severed rope smoking in its serpentine descent. (H. Owen and J.B. Blakeway, A History of Shrewsbury).

Judith Cadman threw down the collecting hat and ran to her bouncing husband in “an agony of grief”, according to the historians. Cadman’s death ended the vogue for ropesliding and the “art of flying”, and no donkey has ascended a church tower since then.

Robert Cadman’s memorial stone, Shrewsbury. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. Photo by Andy Dingley.

References

Paul Sullivan, Bloody British History: Derby (2012)

Stephen Glover, The History of the County of Derby (1829)

https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/weatherextremes/2014/03/10/getting-into-the-archive-shrewsbury-in-the-great-frost-of-1739/

https://singulardiscoveries.substack.com/p/the-flying-man-and-flying-donkey

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Cadman