I was a briefly keen stamp collector between the ages of 9 and 11. It was a male rite of passage, like collecting toy cars and toy soldiers and trying to get excited about football. But of all these hobbies, stamp collecting was the most educational. A well-stocked stamp album was an unblinking window into the world, and the character of the countries that filled it was etched in their stamp designs.

Like many other nations, Britain had a portfolio of stamps that were diverse in shape and subject matter, and my small collection was busy with themes including transport, architecture, wildlife, space travel, Christmas, monarchy, artists, and the 1966 football World Cup final. Britain could get away with this scattergun approach due to its secret weapon – the unifying face or silhouette of the six kings and queens who had reigned since the launch of the prepaid postal service in 1840 and the purchase of my Stanley Gibbons stamp albums in 1971.

These monarchs brought home the reality of the dead British empire, as their inscrutable profiles were also on stamps from Canada, Australia, India, bits of Africa, and islands in the Pacific Ocean whose reality seemed to me as reliable as a promise made in a dream. And these waves of British stamps had been cast upon the chequered pages of our stamp albums and anchored there with sweet-tasting stamp hinges for longer than any other country.

This ancientness gave all the Queen Victoria stamps a whisper of magic. There she was, the first postage queen, hovering above elephants in the corners of old Indian stamps; and there she was again in the local stamp shop in Grimsby, demanding my investment with the same urgency as a school bully requesting your dinner money. This object of my desire featured a simple profile of the Queen’s head, precursor to all those fussy, themed stamps in my album - an origins story, a must-have.

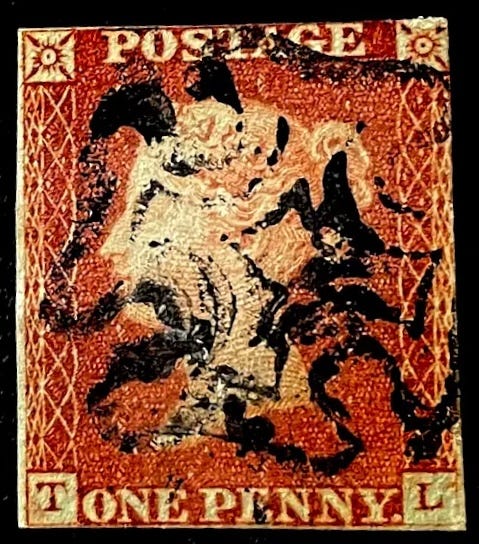

The coveted Queen Victoria in the shop wasn’t the hallowed Penny Black of legend, but a relatively humble Penny Red, with a black ink Maltese cross post mark that had smudged on impact and made a bit of a mess of the stamp (see below). This didn’t bother me, though – I coveted that Penny Red, one of just two in the shop.

Seeing red

For something so groundbreaking, the first postage stamp in the world was delivered surprisingly swiftly. Sir Roland Hill had nudged it onto the UK parliamentary agenda in 1837, and on 1 May 1840, the first Penny Black was printed. Prior to this moment, postage had been paid on delivery, calculated by distance travelled. The new stamps opened up a world of affordable correspondence, to the delight of postmen and the ire of dogs throughout the island.

A competition had been held to design this genre-defining first postage stamp. However, having looked at the 2,600 entries, Roland Hill rejected them all and used a head-and-neck profile of Queen Victoria engraved by Charles Heath based on a sketch by Henry Corbould, which was itself based on a 1834 cameo brooch design by William Wyon that had been used on a commemorative medal in 1837. This copy-and-paste Victoria was used on all British and British Empire stamps until the queen’s death in 1901. Its ghost haunts our postcards and envelopes to this day, as British stamps still incorporate a head-and-neck image of the monarch.

Penny Red prequel - the trailblazing Penny Black, 1840

The Victorian stamp design remains an object lesson in simplicity. The Queen’s head, surmounted by the word ‘postage’, and the amount of pre-paid postage declared as a subtitle. The decoration was minimal, and the letters in the bottom corners referred to the individual stamp’s position on the sheet it was printed on. There was no need to mention the relevant country, as stamps were unique to Britain at this point.

Penny Blacks were only printed for eight months, as it was difficult to see a red ink cancellation mark on the black background, and the red was apparently easy to wipe off, offering the possibility of illegally reusing a stamp. So, in 1841, the Penny Black became the Penny Red (same printing block, different ink), and these were printed from 1841 to 1879, making them a much commoner treasure in the backstreets of Grimsby and elsewhere.

In 1879 the Penny Red was superseded by the Penny Venetian Red, which gave way to the Penny Lilac in 1881. There were several other denominations by that point, but the one-penny stamp family remains the most iconic.

The price tag of the Grimsby Penny Red that dominated my limited ambitions in 1972 was a lofty 30p, which would mean saving my 5p weekly pocket money for six weeks. With my family’s generosity, I only had to save for five weeks, as they chipped in the additional 5p. My grandad commented that I should have bought the stamp earlier that year, before decimalization, when it was priced at 5 shillings (25p).

My prize stamp bore a Maltese-cross cancellation (the official name for a postage mark, the defacement that prevents a stamp from being reused). The two crosses at the top of the stamp show that it was printed before 1864, after which these crosses were replaced with the place-on-the-sheet letters from the bottom of the stamp, in reverse order. This was because cheapskates had been taking the clean top and bottom halves of cancelled stamps and recombining them for an illegal freebie posted letter.

Narrowing the date of further, the lack of perforations on my Penny Red shows that it predates 1850 - before that date, all stamps were cut from the sheet with scissors. But the Maltese-type cancellation cross takes it back even further, as these were replaced in February 1844 by post-marks indicating the post office where the cancellation mark had been applied. So, my stamp is one of the early ones, printed at some point between 1841 and 1844.

Sadly, I soon discovered that, as with many things in life, the journey is more exciting than the arrival. Once my 30p, pre-1844, unperforated, clumsily crossed Penny Red was on display in my stamp album, it looked exactly as I’d hoped it wouldn’t – old, hastily cropped, a little indistinct, artless, and half-hidden beneath the ink mark. Ironically, in attaining the prize, I lost sight of the goal, closing my stamp albums for the last time in 1973.

Navigating via stamps

The messages relayed by the images in my stamp collection lodged in my subconscious, fermenting there in a stew of all the other things my 11-year-old brain had picked up during a rather sheltered childhood. Stamps were mini works of art, enigmatic, enigmatic footnotes to the information available in the atlas.

A map of the world was sobering for a kid weaned on notions of the ‘Great’ in Great Britain. The evidence of the atlas showed that these islands were a tiny afterthought adrift off northwest Europe, while the rest of the world was a huge affirmation of diversity. Former British colonies glowered from the map book as if another world war was just a mispronounced foreign placename away, and the countries of the Commonwealth, old-fashioned enough to keep British monarchs on their coinage and stamps, bulged muscularly from the page as if to say, “Thank goodness we escaped!” Having shed huge chunks of Empire, Britain in the atlas was like a glacier reduced to an ice cube.

But the map told more mysterious stories than the rise and fall of Queen Victoria’s doomed apartheid empire. And nothing in the book was more enigmatic than the huge swathe of pink that hung over eastern Europe like a cloud of poisoned candy-floss. We never talked about the postwar history of those pink bits at school. They had formerly been Empires that routinely fought the British, French, the Ottomans, and each other – Prussia, Austro-Hungary, and Russia. The latter had then amalgamated with its neighbours to become the USSR, and those porous countries nearby had been turned pink by the seeping red of communism. That’s what the school atlas told me, and school lessons added little else to the vacuum. The pink bits were the equivalent of “Here be Dragons” on old maps.

But I knew East Europe better than that, as the countries behind the Iron Curtain had showed me their true personalities through the vibrancy, arrogance, and intrigue of their postage stamps. Queen Victoria and her Penny Reds, Blacks, and Lilacs were iconic, but other countries’ stamps told fascinating, inscrutable, monarchless stories.

So, in spite of knowing very little about anywhere beyond the shores of the British Isles, the 10-year-old 1972 version of me – hooked on T.Rex and Slade, and queueing for three hours at the British Museum to see the Tutankhamun Exhibition – had a pretty clear picture of East Europe and the world based on a ragbag of impressions, inherited prejudices, and - vitally - stamps.

Hungary for more stamps

How stamp-collecting made me foreign

When I next peeked into my musty-smelling early-1970s stamp albums 35 years later and relocated the Penny Red and the rest of the collection to new and more durable books for my sons’ brief interest in stamps, all those childhood impressions of other countries, of foreignness, hit home, and I realised something very profound.

Amidst the utilitarian, small, uniform postage stamps of countries such as West Germany, Switzerland, and Denmark, and the garish, almost ridiculous extravagance of the Middle East’s “Trucial States” stamp designs were some genuine beauties. And many of them came from those pink bits in the map-book, the semi-forbidden Communist countries gathered under the baleful red wings of the Soviet Union. Poland’s stamps were impressive, as were Hungary’s and East Germany’s, but my favourites were Czechoslovakia’s, which struck the perfect balance between tasteful and original.

West Germany - uniform

The Czechoslovakian stamps’ themes were as varied as Britain’s, including Soviet space missions, townscapes, castles and chateaus, wildlife, working class iconography, sporting events, artworks, transport through the ages, civil engineering, and art for art's sake. There was also the alarming spectre of Adolf Hitler, popping up unexpectedly in the 1930s and 40s, before a bland but malign procession of Communist leaders took his place.

A stamp collection is an art gallery, a collection of concise, iconic miniatures. Collected primarily in the late 60s and early 70s, with the bulk of the stamps bought in job-lot bags from newsagents and stores such as Woolworths, and the rest picked up at stamp fairs in Grimsby and Cleethorpes, the majority of my collection had been in circulation in the post-war 1940s through to the mid-60s. This makes them a time capsule of days before photographs were routinely used on stamps.

Czechoslovakia - miniature artworks

Communist stamps turned up regularly in those early ‘70s lucky-dip bags, and by the age of nine, I was mesmerised by these tiny pictorial messages from countries lost in the otherwise unreachable pink bits of the map book.

How far, I now wondered, had that magnificent tableau of Ceskoslovensko stamps, each a compact work of art, prepared me for embracing the enticing, intriguing foreignness of a Czech family, and eventual emigration to Czechia? There was surely a good deal of positive prejudice at play. The notion of “Czech” came preloaded with the notion of something fascinating. I had been introduced to Czech folk-rock in 1997 by a Czech barman, had befriended two Czech girls in Buxton in 1998, and met my Czech partner-to-be the following year. The understated genius of the Czechoslovakian post office had paved the way. My tryst with stamps had not ended with that Penny Red after all.

Love, it seems, is in the stamp album of the beholder.

A lovely read, thank you. I started collecting stamps a few years ago in my 40s. I was kind of concerned that I'd picked up an old person hobby, but like you I love the art work on them and that was my main reason to start collecting. They've taught me a lot about parts of the world I knew very little about. I also discovered that Italian stamps are really rather boring.