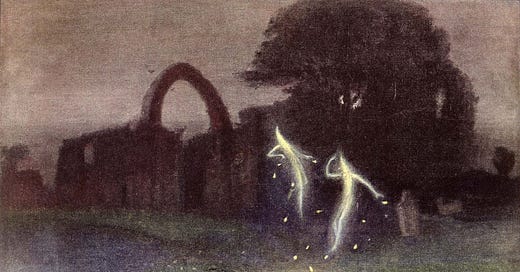

Will-o-the-wisp and snake, by Hermann Hendrich, 1823

In 1965, I had my first encounter with the Lincolnshire marshlands. A branch of the family on my maternal grandfather’s side had resisted the magnetic pull of wartime Grimsby and the Humber and had remained in their ancestral lands in the south of the county, farming crownland in Holbeach St Marks.

On this first visit to their farm, aged three, I was mesmerised by the novelty of geese, chickens, pheasant chicks, rabbits, pigs, and a recalcitrant donkey who would only condescend to pull the cart in which I sat if someone waved a bag of buns in front of its snout. It was like having a zoo in the garden, and I had to be dragged away to sit with the adults for dinner and tea, eager to return to the tame wildlife.

But the wilderness of Holbeach Marsh, within whose 60 square kilometres Holbeach St Marks and Holbeach St Matthew sit like last survivors on a sinking ship, was a different world altogether. After a ten minute walk across the fields from the farm, the reek of old cabbages gave way to the sour, savoury whiff of mudflats, sea, and dead shellfish. Crab shells poked from the thick silt like disinterred alien corpses, tufts of samphire spiked the mud like soggy cactus, and lugworms were dredged from the silt by a frowning man armed with a child’s seaside spade.

I was relieved when we backtracked to the sanctuary of the farm, but a small party of pheasant-shooters had installed itself at the dining table, and their unprovoked, brusque questions were intimidating for a wee lad unaccustomed to unfamiliar faces. I clung to mother’s skirt and waited for the social storm to pass.

Samphire and shellfish

When we revisited Holbeach St Marks in 1967, I was five and much wiser than before. I knew this time that the farm and its animals were the main playground but that the real magic was out there on the Marsh, which had stuck in my head like an ambivalent dream these past two years.

I was taken there this time by Ros, the unmarried eldest daughter of the household. She had a perfunctory manner, a restless impatience, and a surly demeanour intended to discourage small talk or affection. She was the most self-contained and self-sustaining person I had ever met, at once aloof and up to her knees in the Lincolnshire clay.

“Come on then, young ‘un. It’s a long walk”, she said. I asked her if I could collect shells and crabs, and she fetched a Tupperware box from the pantry, handing it to me without comment.

It was a big box, and I managed to stuff it with cockle, mussel, and razor shells, a couple of whelks, and dozens of small crabs, crab legs, and legless crab shells. Some were white, some green, some brown. There were enough bits here to assemble a crab army, and I looked forward to finding a quiet spot in the garden to create this necro-crustacean battalion, hoping that Sandy the farm Labrador wouldn’t decide it was edible.

Holbeach St. Marks. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license. Photo by Peter Latham

Ros marched me across the Marsh, on a mission to collect samphire as a side dish for the evening meal. Everyone seemed to prize this saltmarsh delicacy, and it was sold at local markets for a surprisingly high price. To me, its promising crunch delivered a disappointing hint of salty lettuce, and it tended to be dunked in plenty of brown sauce before making it from fork to mouth.

While Ros plucked samphire, I watched the gulls shimmer over the distant sea. A couple of crows. Some pigeons and sparrows. Summer was not the heyday for birdwatching on the Marsh. With my box of calcium carbonate and chitin filled long ago, I was relieved when Ros barked, “Back home then, young ‘un!”.

“What you gonna do wi’ them crab bits?”, she asked. I told her I planned to reassemble them and have a battle, mollusc against crustacean. “Mek sure your Mam dun’t see”, she said, although I failed to see why this precaution would be necessary.

Foolishly, I thought my mother would be impressed with my haul from the deadlands of the Marsh. She had, after all, brought me here and allowed me to go crabbing with Ros. But I was rudely awakened. Mother eyed my Tupperware body bag with horror, confiscated it, and told me to wash my hands before some terrible sickness seeped from the crabs via my fingers to my digestive system. I never saw the shells and crab bits again, and tears were in vain. Mother’s tunnel-visioned focus was on my health and wellbeing. Had I been older and wiser, I would already have gathered this from the scrubbed hands and disinfected work surfaces of home, and the warnings of “Don’t go near the edge!” (of anything – ponds, walls, roads, lawns, doorsteps. Not cliffs – I was never allowed anywhere near anything genuinely high and dangerous).

The crabs were a tragic loss, but the haunting Marsh stayed with me. That’s what hauntings do, after all. The smell, the colour-shy greys and browns, the occasional sharp green of the samphire and grasses, the squat, bristling sea holly, the mushy footprints of lugworm-diggers, the huge sky, the endless flatness.

Not too long ago, this had been a landscape of water – fen and marsh, barely dry for long enough to enable Hereward the Wake to retreat to Crowland or Ely. It was a land as reliable as a malign god in a fairy tale. Dryness was a reluctant and fleeting visitor here, and its folklore was soaked in that damp spirit.

The Strangers

When reading local folk tales of the fens and marshes in later years, I conjured an image of Holbeach St Marks, with its vast acres of crops and pheasant copses forming a borderless, dyke-cut, arable bog, redbrick farmhouses teetering on hummocks that rose no more than six feet above sea-level. The scene was vivid in my mind, coloured by my childhood visits.

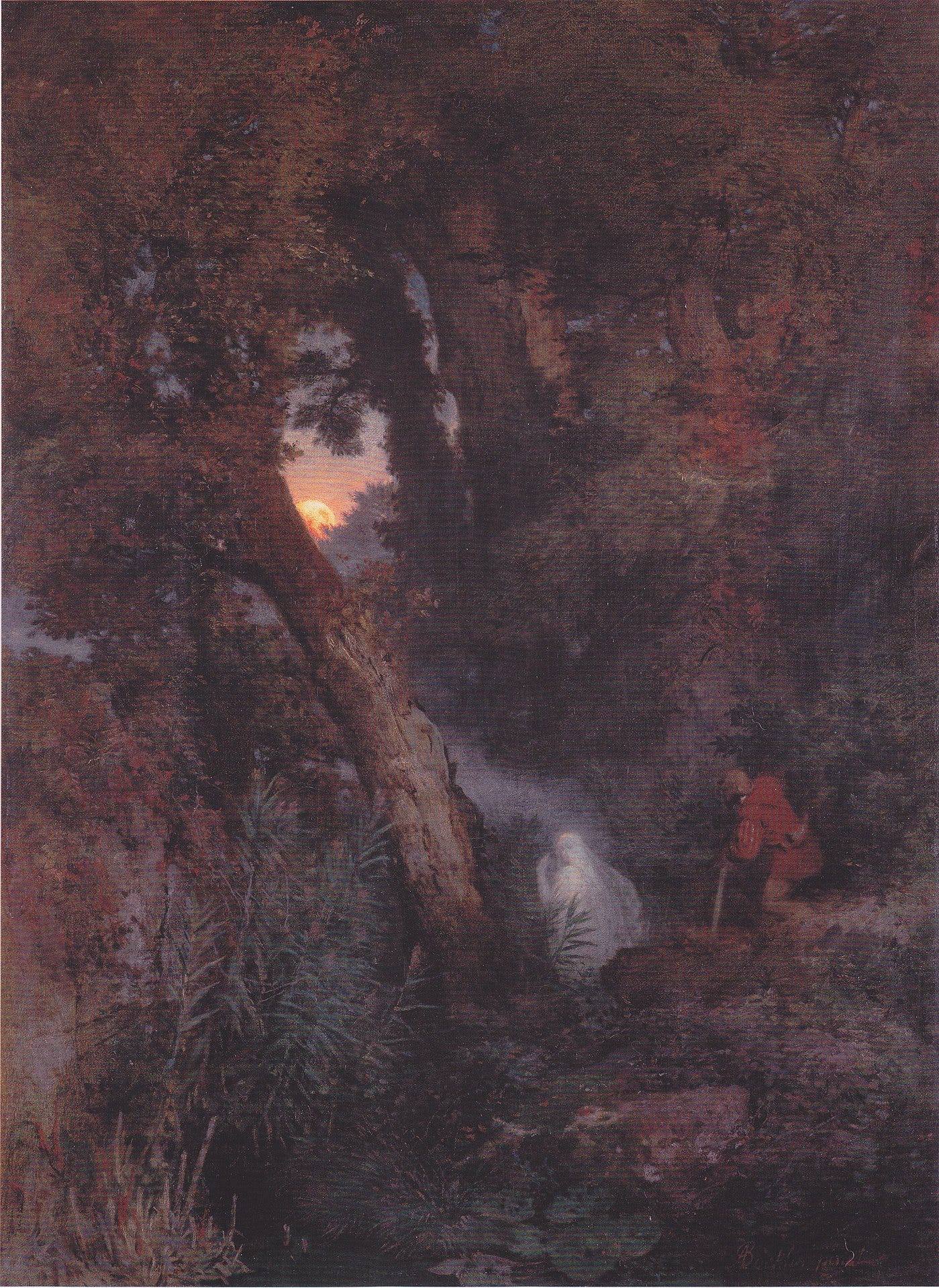

The farmers and villagers in the old tales were wisely fearful of the Bogles that lurked, Grendel-like, in the wasteland. They appeased them with offerings and rituals, but I imagine these semi-aquatic faerie folk were unappeasable. They were as miserable and fearful as their human neighbours, splashing flat-footed through the fen, keening in the wind off the sea, irritated by the marsh-gas-light of the Will o’ the Wisps, and ducking their heads in the stinging mud as the whistling and piping ghosts with curlew heads flew overhead.

An 1862 oil painting of a will-o'-the-wisp by Arnold Böcklin

These discontented Bogles, no higher than a span, were often called The Strangers, as it was bad luck to call them by their true name (whatever that might have been). Other euphemisms included Tiddy Ones, Yarthkins, and Greencoaties. As the latter name hints, they wore green, with yellow toadstool-cap-like bonnets. They had wide mouths like frogs, long beak-noses and spindle-thin limbs like wading birds, huge red tongues like cows, and big, flatfish-like hands and feet. Their voices were described as ‘girns and yelps like an angry hound’, but when happy, they whistled like Peewits and twittered like small birds. The Strangers enjoyed dancing in the moonlight on the flat stones used by their human neighbours to make offerings of first fruits, first corn, first beer, and fresh blood.

Preeminent among The Strangers was a faerie king of sorts, known, again euphemistically, as Tiddy Mun, meaning little man. If Tiddy Mun had a bone to pick with you, it was bad news. He was in charge of the water levels and maintained the general health of the wetland and its inhabitants. Once the draining of the fens and marshes began in earnest in the 17th century, Tiddy Mun bowed out ungraciously in a fog of pestilence and death, and the marsh men and fenlanders mourned the loss of the old, semi-aquatic Lincolnshire. With its draining, they had lost not just their ancestral bogs, but the good will of The Strangers and the swirling mythology and folklore that went with them.

A generation that had never left offerings for Tiddy Mun and the Bogles took over the land and poured scorn and forgetfulness on the whole soggy business.

The Dead Moon

Such was the grim fame of the Strangers/Bogles in their heyday that the Moon decided to spy on them. She wrapped herself in a cloak of black clouds and descended to the marshes, following the lantern flames of the Will o’ The Wykes (local name for will o’the wisps) that shifted through the wetlands, and letting her face and golden yellow hair shine on the disgruntled Bogles and other bogland spirits. She stayed too long in the watery maze, however, and one of the stones she stepped on wobbled and tipped her into the bog, where willow roots pulled her down. The Bogles covered the drowning Moon with a large flat stone and set a troop of Will o’ The Wykes to guard her graveside.

Emboldened by the thick murk of the following nights, the Bogles roamed further afield, raiding farms, chasing humans and livestock, and ignoring all attempts to appease them with spells, charms, or offerings of food and drink. Their reign of darkness lasted for a month, until a wise woman told the marsh folk to search for the dead Moon. Taking their torches, and armed with spells and incantations, they found the lunar grave, fought off the Will o’ The Wykes who guarded it, and hauled the stone aside. The Moon immediately rose into the air in a tremendous blaze of light and life, and the Bogles and creatures of the night scattered. The triumphant marsh men made their way home by the bright moonlight, and…

…That was that. I’m leaving it there before my prose purples even further. The tale of the Dead Moon is intriguing, more like an origins myth (i.e, explaining the monthly cycle of the moon) than a fairy story. It could only have been imagined in the pre-drainage otherworldliness of the fens and marshes.

It’s also a contentious piece of folklore, too perfect to be true. The tale was collected in the late 19th century by Marie Clothilde Balfour, who noted it down from a nine-year-old girl. Most of the folklore of the Strangers comes from Balfour’s Legends of the Carrs, and there is surely a rich dose of embellishment and wishful thinking in the stories she relays, as if Balfour had been possessed by the spirit of that original historical fabulist, Geoffrey of Monmouth.

The fact that we want to believe the folklore is genuine doesn’t make it so. But I’ve suspended disbelief since first meeting the legends in 1977 in Katherine Briggs’s Dictionary of Fairies, so I’ll persist in my wishful thinking to the bitter end.

In the light of these tales of unhappy and covetous Bogles, Strangers, Tiddy Ones, and Will o’ the Wykes, the fate of my crab-and-cockle haul made more sense. I had stolen treasure from the Marsh and my canny mother had rectified the situation without fuss. Food-poisoning via crabby fingers was one thing; the damp faerie host of the Marsh was a different level of nightmare altogether.

Norfolk Samphire (Saliconia Europaea)

References

Katherine Briggs, A Dictionary of Fairies, 1977

Marie Clothilde Balfour, Legends of the Carrs, 1891