The Dodo – the Most Extinct Thing in the World

Putting the flesh back on the bones of a legendary bird

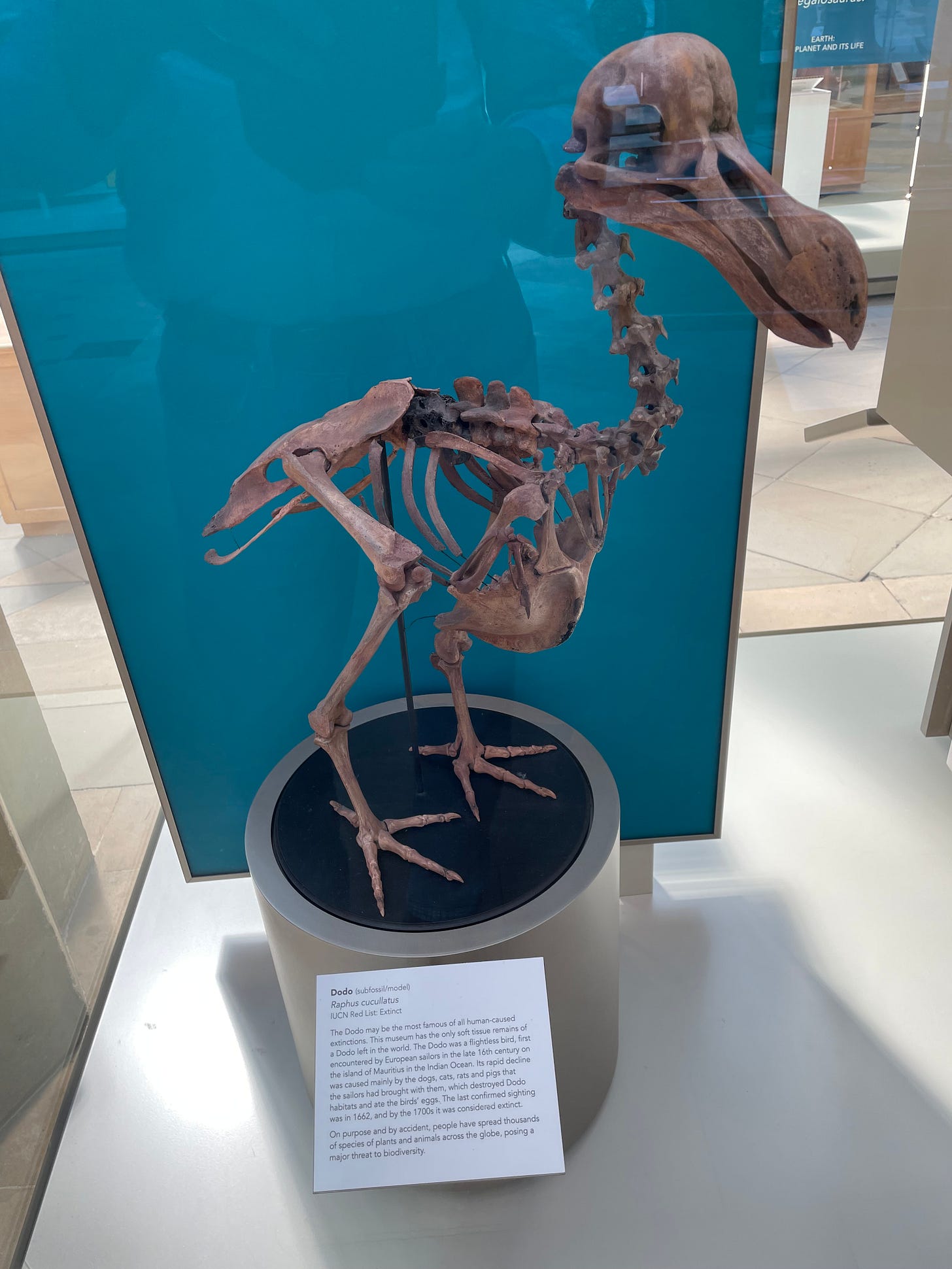

Reconstructed Dodo in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

For many decades, I have been telling people that the Dodo (Raphus cucullatus) has been described as “the most extinct of all extinct animals”. This epithet resonates because the poor bird – a giant, flightless pigeon trapped on an island in the middle of nowhere like a portly tourist following the collapse of a package holiday company – has come to symbolise the very concept of extinction. Anything “as dead as a Dodo” is as irredeemably lost as it is possible to be.

The bird’s status as the ultimate extinct bird was reinforced by its adoption as the logo of The Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, (formerly the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust), established by Jersey Zoo founder, naturalist, author, bon viveur, and champion of captive breeding, Gerald Durrell. But apart from Jersey and the bird’s native island, Mauritius, it is Oxford that will be forever associated with the Dodo. This is on account of of three iconic pieces of dodobilia – a specimen of the bird that came to the city via a 17th-century cabinet of curiosities that formed the original nucleus of the Ashmolean Museum; John Tenniel’s drawings of the Dodo in Alice in Wonderland; and a 17th-century oil painting of the bird by Rolandt Savery, which hangs in the city’s natural history museum.

There were, however, even earlier Oxford Dodo specimens, kept in the University’s Anatomy School at Christ Church College. At the time of the Restoration (1660), the college’s collection included two stuffed Dodos that have, sadly, long since disappeared.

The Oxford Dodo was initially the London Dodo, a living bird displayed to paying customers at a site near Lincoln’s Inn Fields, possibly shipped to England in 1628 by English diplomat Emmanuel Altham. This bird was seen by writer, theologian, and owner of a name that makes you suspect a hoax, Sir Hamon L’Estrange in 1638. He commented:

About 1638, as I walked London streets, I saw the picture of strange looking fowl hung out upon a cloth and myself with one or two more in company went in to see it. It was kept in a chamber, and was a great fowl somewhat bigger than the largest turkey cock and so legged and footed, but stouter and thicker and of a more erect shape, coloured before like the breast of a young cock pheasant, and on the back of a dun or dark colour.

After death, the Dodo was stuffed and became part of Tradescant’s Ark, a cabinet of curiosities-type museum in Lambeth kept by John Tradescant, naturalist (and Charles I’s gardener), and then by his son, another John Tradescant. The Ark became the first museum in England open to the public, under the name Musaeum Tradescantianum. The bird was described in its catalogue as “Dodar from the island Mauritius; it is not able to flie being so big”. The Dodo was acquired in 1662, along with the rest of Tradescant’s Ark, by Elias Ashmole, founder of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum.

Bone jigsaw - a rebuilt Dodo in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

Extinction – the Ashmolean years

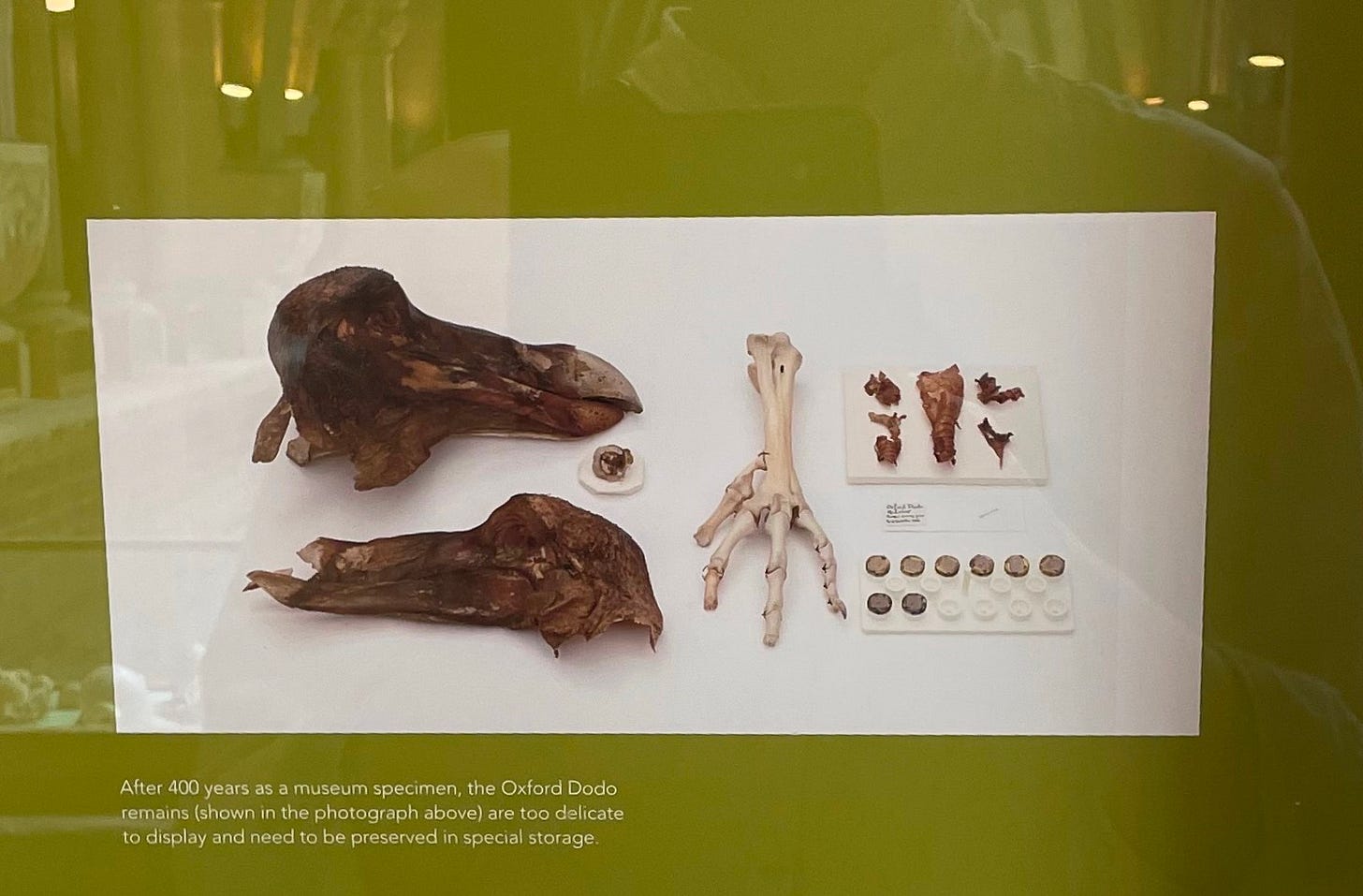

By 1755, quietly decaying in storage at the Ashmolean, the Dodo was in such a sorry state that the body was burnt, with just the head and legs preserved. The ravages of time, the carnivorous efforts of stuffed-animal-loving Dermestes beetles, and the relatively primitive nature of contemporary taxidermy, left the curator with little choice.

(Robert Gunther, founder of the Museum of the History of Science (which occupied the Old Ashmolean building in 1926), was having none of this, however. He called the destruction of the Oxford Dodo an act of wanton vandalism, symbolising all that was bad in museum management. It seemed to anger him more than the extinction of the animal itself, and he judged the disposal of the rotting bird symptomatic of the Oxford’s neglect of science, a weakness, said Gunther, created by the University’s stifling love of classical archaeology to the exclusion of all else.)

The scant remains of the museum’s Dodo were rediscovered in 1818, by which point its very existence had become an object of speculation. In 1847, Sir Henry Acland, an anatomist and physician based at Oxford's Christ Church College, decided to dissect the sorry carcass. He removed the skin from half the bird’s head, making the astounding discovery that beneath the skin lay the skull. I assume Acland won that year’s prize for taking unnecessary measures to reveal the blindingly obvious.

However, the remaining scraps of bird were not actually put on display until the opening of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History in 1860. On the one hand, visitors finally had a chance to see the the world’s only surviving mummified Dodo body parts; on the other hand, the effects of neglect, beetles, etc., had reduced them to something that redefined the word ‘pathetic’. These relics had once been part of the world’s only stuffed Dodo, and yet time and ineptitude had reduced them to shrivelled remnants that looked more like something discovered in a box of discarded KFC.

An early scientific name for the Dodo, applied by animal-and-plant-namer-extraordinaire Carl Linnaeus, had been Didus ineptus, meaning “inept/clumsy dodo”. It is therefore ironic that Homo ineptus had made such a mess of this last specimen. Linnaeus was no stranger to ineptitude – his original name for the Dodo was Struthio cucullatus, Struthio being the Latin name for the Ostrich. Others had placed the Dodo tentatively in other groups, including pheasants and turkeys, plovers, and albatrosses. Esteemed and arrogant biologist Richard Owen believed it was a type of vulture. Johannes Theodor Reinhardt of Copenhagen and English zoologist Hugh Strickland were the winners of the Dodo lottery, successfully identifying it as a very strange type of pigeon.

Hillaire Belloc commemorated the Oxford Dodo in his Cautionary Verses (1907):

The Dodo used to walk around

And take the sun and air.

The sun yet warms his native ground -

The Dodo is not there!

The voice which used to squawk and squeak

Is now for ever dumb –

Yet you may see his bones and beak

All in the Mu-se-um.

Even this is an exaggeration, though – as noted above, it was just the head and feet of Tradescant’s bird that survived the twin ordeals of time and fire.

Cast of the Oxford Dodo’s head, plus other scraps

The song and dance of the Dodo

The question of what exactly the Dodo would have looked and sounded like in life has taxed inquiring minds down the years. This giant, flightless pigeon was discovered by Europeans on Mauritius in 1598 and extinct by 1690. Early sketches suggest a much thinner bird than the ones immortalised in the original Alice in Wonderland and other portraits—something more akin to the Crowned pigeons (genus Goura) of New Guinea, perhaps, albeit with a larger head and beak.

However, genetic analysis published in 2024 revealed that the Dodo’s closest living relative was the Rodrigues solitaire (Pezophaps solitaria), which became extinct c/o humans around 1750. The Dodo and the solitaire were placed in a new avian family, Raphina subtribus nova, in recognition of this unique kinship.

Birds of a feather - the equally extinct Rodrigues solitaire

There are three contenders for the etymology of the word dodo. The Portuguese “doudo”, meaning “idiot” is a prime candidate, as is the Dutch “dodaersen”, meaning “fat arse”. But I love the idea that the name might be onomatopoeic, a rendition of the bird’s call. If a cuckoo can say “cuck-oo”, a peewit “pee-wit”, and a Hoopoe “hoo-po”, a Dodo can surely say “do-do”.

Not many contemporary pictures of the bird survive, for it was extinct by 1680. This was probably an early example of conservation’s recurring nightmare – the depredations of introduced alien species. Europeans brought dogs, cats, pigs, and monkeys with them to Mauritius, and these, together with stowaway rats, ate eggs and young birds, sending Dodo numbers into rapid decline. Contrary to popular belief, the species was not exterminated for the cooking pot: the Dodo’s flesh was, apparently, not very palatable. Not that this stopped the invaders from clubbing the slow-moving, trusting animals over the head with large sticks, of course – the kind of casual carnage that has been Homo sapiens’ trademark greeting after landfall on many occasions over the last 15,000 years.

The ‘fat Dodo’ painting in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History is by Jan Savery, a Flemish artist who produced the work in 1651. There were still dodos alive at this time, and Savery’s painting is probably based on a captive bird, one that had doubtless been overfed and under-exercised. This overweight specimen became the template for future depictions of Dodos. For example, George Edwards’ 1759 painting (there is a copy in the Museum, and the original can be seen in the Ashmolean) was the basis of John Tenniel’s Dodo drawings in Alice In Wonderland.

Edwards’ (left) and Savery’s (not left) Dodo paintings in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

To put things straight, the Museum displays a slimline reconstruction of the Dodo based on current scientific thinking on how bones relate to body mass. The reimagined bird was created by taxidermist Derek Frampton in 1998, and it stands alongside a complete skeleton pieced together from surviving bones, with a few man-made ones added to fill in the gaps. You may be disappointed to learn that the ‘Oxford Dodo’ head on display in the museum is a cast, the original parts safely tucked away in store. There’s not much of it – just a skull and beak with some shriveled skin. The bird was apparently shot in the back of the head sometime around 1640.

Alice and me in Dodoland

Alice Liddell saw the head and feet of the Oxford Dodo on a trip to the Ashmolean with Charles Dodgson in the early 1860s. The latter, suffering a stammer, instantly became nicknamed Do-do-Dodgson, and, under his nom de plume Lewis Carroll, he immortalized Liddell and himself (as a Dodo) in Alice in Wonderland, published in 1865. The bird does not say very much in the text, but its first words could be taken as a rallying call for future efforts to prevent other species becoming ‘as dead as a Dodo’:

“In that case”, said the Dodo solemnly, rising to its feet, “I move that the meeting adjourn, for the immediate adoption of more energetic remedies”.

Having decided to begin this article with that quote about the dodo being the most extinct of all extinct animals, I was perturbed to find that nobody appears to have said it. Dead-end Internet trails led me to Douglas Adams, who wrote about the Dodo in his wonderful book Last Chance To See but did not use the “most extinct” phrase. Another trail led me back to Gerald Durrell, whose Wildlife Trust and zoo had adopted the Dodo as their logo in the 1950s. I rummaged through my extensive Durrell collection (he being one of the few authors whose output I own in its entirety). But I couldn’t find this elusive quote about the Dodo being more extinct than anything else.

Had I made it up? It seems unlikely. Had I misremembered or conflated words I had read 40 or 50 years ago? That seems likelier. However, I'm still convinced that somewhere out there, probably in one of the more obscure appendices of a Durrell book, those moving words exist. If not, let's mull them once again, one last time:

The dodo is the most extinct of all extinct animals.

There can be fewer things sadder than that.

References

Errol Fuller, Extinct Birds, 2000

Charles Norton, The Last Dodo, History Today, April 2013

David Quammen, The Song Of The Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinctions, 1997

R.F. Ovenell, The Ashmolean Museum, 1683-1894, 1986

A. V. Simcock (ed.), Robert T. Gunther and the Old Ashmolean, 1985

https://oumnh.ox.ac.uk/learn-the-oxford-dodo

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/20/science/archaeology-dodo-extinction.html